Hey Guys,

To everyone who's been following along these last few weeks, I really appreciate it. Recently, though, I've been doing some film work of my own, as well as starting a part-time job to feed my broke ass while I take on unpaid film gigs and build my resume.

The point is, I don't think I'll have time to consistently publish three posts a week. But I'm going to try to keep putting up an op-ed piece every Friday, and reviews whenever I get the chance. Follow this blog if you want to be notified of new posts.

Thanks again!

I'm like every other movie critic. Except I'm also an out-of-work filmmaker who's too broke to see movies all the time. So if I tell you a movie is worth ten bucks, you know I mean it.

See This Tonight updates every and Friday, and intermittently on other days.

It is my sincere belief that the reproduction of copyrighted materials on this page for the purposes of criticism constitutes fair use.

Tuesday, August 24, 2010

Friday, August 20, 2010

3 Noteworthy Acts of Badassery in Movies with High Artistic Value

I strongly suspect that there are a lot of casual moviegoers (especially males 18-34) out there who would like to be more "cultured" when it comes to movies, but are scared that 'cultured' means watching boring movies.

I'm here to say that it doesn't have to. My goal in the next thousand words or so is to give typical guys an access point to the world of high art cinema. By 'access point,' I mean something that can hold one's interest long enough for one to learn to appreciate the artistic value. And that access point is badassery. By 'badassery,' I mean the practice or state of being a stone cold, bona fide Bad Ass. What follows is a list of my three favorite examples of movies with enough artistic value that you can mention them around academic film snob types and be taken seriously, but that also include at least one moment of epic badassery.

[Note: By directing this post at male demographic, I don't mean to imply that women don't value or can't appreciate badassery. It's just that, if we're dealing in broad generalities, badassery is a particularly good access point for adult men. And I'm sure I'll catch some slack for only listing male characters, but there's a very contentious debate about whether it's even a good thing for female characters in movies to act like male action heros. So I'm sticking to male characters in order to steer clear of this debate. At least for now...]

3. Don't EVER leave James Dean alone with your girlfriend. Even if you're dead.

The Caveat: You'll have to put up with the score, which in this day and age sounds a little hokey. But bad-ass never goes out of style.

1. Clint F***in' Eastwood.

I'm here to say that it doesn't have to. My goal in the next thousand words or so is to give typical guys an access point to the world of high art cinema. By 'access point,' I mean something that can hold one's interest long enough for one to learn to appreciate the artistic value. And that access point is badassery. By 'badassery,' I mean the practice or state of being a stone cold, bona fide Bad Ass. What follows is a list of my three favorite examples of movies with enough artistic value that you can mention them around academic film snob types and be taken seriously, but that also include at least one moment of epic badassery.

[Note: By directing this post at male demographic, I don't mean to imply that women don't value or can't appreciate badassery. It's just that, if we're dealing in broad generalities, badassery is a particularly good access point for adult men. And I'm sure I'll catch some slack for only listing male characters, but there's a very contentious debate about whether it's even a good thing for female characters in movies to act like male action heros. So I'm sticking to male characters in order to steer clear of this debate. At least for now...]

3. Don't EVER leave James Dean alone with your girlfriend. Even if you're dead.

The Movie: Rebel Without A Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955)

The Artistic Value: Stewart Stern's screenplay about disaffected youth is a masterpiece, and Ray executes it like a master. The clothes and slang seem old-timey when you watch this movie today, but its dramatic core will keep it relevant for as long as teenagers are pissed at their parents (i.e. forever). And if you're willing to read between the lines a little bit, it touches on some subject matter that mainstream America in the 50's was NOT ready to talk about explicitly (e.g. homosexuality, incest).

The Man: In the 50's, when you thought 'Bad Ass,' two men came to mind: Marlon Brando and James Dean, and each had his own brand of machismo. Brando was the kind of macho that seemed like he came out of the womb throwing punches, whereas Dean was the sensitive guy who had to learn to get tough real quick because everyone always messed with him. If 70's rock analogies help you as much as they help me, James Dean was the Bruce Springsteen to Marlon Brando's The Clash.*

The Badassery: There's a PSEUDO-SPOILER coming up, but I'll try and do this without giving away too much plot. About halfway through the movie, James Dean's character gets caught up in a dangerous dare with the school alpha male. By a complete accident, the alpha male dies. Within minutes of his death, Jimmy starts macking on the dead guy's girlfriend. Successfully. Take a few minutes to process that.

|

| Kind of like that, except not played for laughs. |

2. Max von Sydow is the Swedish Chuck Norris.

The Movie: The Virgin Spring (Ingmar Bergman, 1960)

The Artistic Value: Ingmar Bergman is probably the greatest and most important director that you've never heard of unless you went to film school. But lots of people whose movies you have seen were really into Bergman. And if your mental image of an arty movie involves people with nihilistic attitudes, photographed in black and white, talking in a foreign language about very serious things, you have Ingmar Bergman to thank. But seriously, the man was a master of his craft who made some of the most gut-wrenching dramas of all time. If you can have an intelligent conversation about one of his movies, any film snob will take you seriously. Also, his 1957 film The Seventh Seal invented the cliche of a man playing chess with death incarnate.

The Man: Max von Sydow is a Swedish actor who speaks Swedish, Norwegian, English, Italian, German, Danish, French and Spanish. You may recognize him as Father Merrin in The Exorcist, but before that, he made an insane number of movies with Ingmar Bergman. I'd say more about him, but all you really need to know is summed up by his facial hair in The Virgin Spring.

|

| Would you mess with this dude? I didn't think so. |

The Badassery: Again, I'm going to try not to give too much away, but if you've seen The Last House On The Left (Wes Craven, 1972) or its 2009 remake, you already know the plot. Suffice it to say, Max's character realizes he has some murdering to do. But, being a good medieval Christian, he decides his murdering must be accompanied by some preemptive repentance in the form of self-flagellation. And of course the best way for a medieval Swedish farmer to flog himself is with the branches of a birch tree. And what's the best way acquire birch branches? If you answered 'axe,' congratulations. You're a sissy. Max von Sydow walks out into the countryside and removes a full-grown birch tree from the ground with his bare hands. Now, one of the most pervasive theme in Bergman's oeuvre is man's noble struggle against forces outside of his control. And on the one hand, the scene I've just described is a brilliant metaphor for that struggle. On the other hand, it's a dude wrestling with a tree and winning.

The Caveat: The Virgin Spring has a bad-ass climax, but be prepared for A LOT of talking leading up to it.

The Caveat: The Virgin Spring has a bad-ass climax, but be prepared for A LOT of talking leading up to it.

1. Clint F***in' Eastwood.

The Movie(s): Sergio Leone's "Dollars" Trilogy: A Fistful Of Dollars (1964), For a Few Dollars More (1965), and The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly (1966)

The Artistic Value: Sergio Leone's epic trilogy ushered in a new style of western, usually called "Spaghetti Westerns," because they were shot in Italy with Italian crews. That's because Leone was one of the most innovative visual thinkers of the last 50 years. His style was marked by the juxtaposition of gritty, extreme close-ups of grungy cowboys with gorgeous, idyllic vistas of the American West (or rather, the Italian countryside made to look like the American West).

The Man: Before he got noticed by Leone, Clint F***in' Eastwood starred on the TV series Rawhide. After his three films with Leone, he played Harry Callahan in the Dirty Harry series, and then went on to direct several artistic bad-ass films of his own, including Unforgiven (1992) and Gran Torino (2008).

The Badassery: Of the three films listed, The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly has the most moments of staggering badassery (the badassery is so consistently epic that the American Civil War is a minor subplot), and For a Few Dollars More probably has the greatest average of badassery per minute. But the single most bad-ass moment of the trilogy happens early on in Fistful Of Dollars. For reasons I won't divulge, his character needs to get in good with one particular gang. To do this, he tracks down four of their rivals on the rivals' home turf, and singlehandedly guns them down. His stated reason for the attack: they made fun of his mule when he rode into town.

The Caveat: Leone's westerns consist of pretty much three things: Breathtaking landscapes, murder, and discussions pertaining thereto. The discussion parts can get a little slow sometimes. But then Clint Eastwood blows up someone's horse by lighting a cannon with his cigar and everything is okay.

Honorable Mention: Akira Kurosawa

Kurosawa is the father of serious Japanese cinema. Not all of his movies are bad-ass, but he gets an honorable mention because Fistful of Dollars is basically a remake of his samurai classic Yojimbo (1961). Also, the American western epic The Magnificent Seven (John Sturges, 1960) is a remake of Kurosawa's Seven Samurai (1954). Oh, and Star Wars: A New Hope (George Lucas, 1977) borrows heavily from Kurosawa's Hidden Fortress (1958).

Let me wrap up by introducing the first Superlative that I hope will appear regularly on this blog: The Official Tim Campbell Seal of Approval.

The Official Tim Campbell Seal of Approval is named after my friend, Tim Campbell, who only likes movies if he deems them manly enough. Therefore, the Official Tim Campbell Seal of Approval will be bestowed upon films with extraordinary levels of sustained badassery. Leone's "Dollars" Trilogy are the first three films upon which I will bestow this award.

So in closing, the next time someone tells you you should be more cultured when it comes to film, remember the words of Leonidas in 300 with regards to all the soldiers he and his Spartans kill: "We've been sharing our culture with you all morning."

*Before I piss off any Bruce nuts, I'm aware of the quote from "It's Hard To Be A Saint In The City." But he says he walked like Brando, not that he was Brando. Cf. the "learned how to walk like the heroes we thought we had to be" in "Backstreets."

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

MYSTERY TEAM (Dan Eckman, 2009)

Laughs: 10/10

Story: 7/10

Cinematography: 8/10

The Sugar: The kind you'd find in a good sweet tea

The Sulphur: Sulphur

The Bottom Line: Mystery Team is the funniest movie I've seen in a while. See this tonight.

I went into this movie knowing there was a lot of potential for disappointment. Derrick Comedy might be the best sketch comedy troupe on the internet. They're my favorite, in any case. But up until Mystery Team, everything they'd ever done together had been under ten minutes, and I was scared that they wouldn't pull off the transition from short-form to feature-length. But they stepped up like champs and made something that's more rewarding than, and at least as funny as (if not funnier than) their best internet sketches.

As children, the Mystery Team, that is, Jason (Donald Glover), Duncan (DC Pierson), and Charlie (Dominic Dierkes) became local celebrities by solving Hardy Boys-style mysteries around their small New Hampshire town. Now that they're seniors in high school, everyone around them has grown up, but they're still exactly the same. No one takes them seriously, of course, because their exploits, vocabularies, and interests (at least at the start) are still those of children. But when a young girl asks the Mystery Team to investigate the murder of her parents, Jason sees a golden opportunity for the team to regain credibility. And it doesn't hurt that the young girl's older sister just made Jason realize that girls aren't icky. )After all, what would a detective caper be without a good-lookin' dame?) As you'd expect, the three boys are in way over their heads, even more so than the average high schoolers would be investigating a double homicide. And that's where most of the humor comes from in this movie.

And it most definitely is humorous. You will laugh. Alot. I laughed so frequently and loudly that I felt like a crazy person watching it by myself. I should mention that, even though this is a movie with three very child-like protagonists, this is not a movie for children. It's got more than its fair share of cursing and sex jokes, and there's a bit of violence, nudity, and scatological humor (think Trainspotting but played for laughs) thrown in there for good measure. But the whole crux of this movie and its humor is the way a few very naive characters get thrown into a very grown-up world.

The Derrick Comedy bunch also deserves some credit for their writing. There's a very common pitfall among feature films made by sketch comedians. Namely, they have a difficult time integrating their humor into a coherent story. You know what I'm talking about. You'll be watching the movie and then all of a sudden it seems like the plot gets put on pause for five minutes so the performers can go into a sketch. Even geniuses like Abbot & Costello and the Monty Python guys often fell into this trap. And while I'm not suggesting that the Derrick crew is on the same level as those legends, they did manage to avoid this trap; the humor in Mystery Team flows pretty organically from the plot.

And Eckman deserves props for directing and editing. I can tell you from my own experience, it's really difficult to wear both of those hats. Often, making the best editing decision for the movie overall requires scrapping footage that took a lot of blood, sweat, and tears on the part of the director to get. And when you, as the director, are also editing, it can be really tough to have to kill your baby, so to speak. Looking at the deleted scenes on the DVD, I can tell that Eckman had a ton of hilarious improv footage that he must have felt very tempted to include in his movie. But, for the most part, he had the resolve to cut some bits short in order to keep the plot moving at a good pace. Also, Austin F. Schmidt did a nice job photographing this movie. I found the glow effect a little much at times, but overall his shot choices were surprisingly elegant.

All in all, this is a movie I would immediately recommend to my friends. But if you're not sure whether Derrick Comedy's brand of humor will rub you the right way, here's one of their internet sketches:

If you found that funny, then you have to see Mystery Team tonight.

Patience Is A Virtue

I'm sure many of you wake up early on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays to read my blog and are absolutely crushed if there isn't a new post. But fear not, I haven't forgotten about you. I've been completely swamped working on some projects of my own (you know, actually making movies instead of telling other people how to make theirs better) and have gotten a little behind on my writing here. But I'm aiming to have a post up a little later today, so check back this evening and everything will be right in the world.

Monday, August 16, 2010

SHADES OF RAY (Jaffar Mahmood, 2008)

Writing, Acts I & II: 4/10

Writing, Act III: 7/10

Overall Originality: 8/10

Quirkiness of Supporting Characters: 9/10

Minutes Before Men In The Audience Realize With Horror That They're Watching And Enjoying a Romantic Comedy: 75/90

That said, let's talk about this movie. Ray (Zachary Levi, who looks strikingly like an Israeli version of John Krasinski) is an aspiring actor with a white mother and a Pakistani father (Brian Geoge, a.k.a. Babu from Seinfeld...nice to see he's still getting work). His father has always cautioned him against marrying any woman who is not Pakistani. If you've been following along, you'll realize how well Ray's father followed his own advice. Nevertheless, Ray has just proposed to his white girlfriend, who can't say yes until she's talked it over with her presumably xenophobic parents. While Ray waits for an answer, though, his parents' marriage starts to dissolve. And as part of a deal he strikes to get his father to try and reconcile with his mother, Ray agrees to go on just one date with a Pakistani woman of his father's choosing. Without spoiling too much plot, I can say that they kind of hit it off, and things get a bit complicated for Ray. Then again, things have always been a bit complicated for Ray. As a self-described "mutt," Ray has never really been sure what to make of his ethnic identity, and this tension underlies all the other conflicts of the film.

Before I start my nitpicking, let me say that I genuinely enjoyed this movie. When it starts, though, Shades of Ray doesn't seem completely certain what kind of comedy it wants to be. Sometimes it tries to be a subtle, family-driven romantic comedy with psychologically realistic characters and other times it tries to be a zany, slapstick comedy with over-the-top characters. Both are equally legitimate forms of comedy. But each is watched and identified with differently, and when a single movie tries to do both, it can be hard for an audience to get its bearings. Don't get me wrong, both the zany bits and the subtler jokes are quite funny in and of themselves. But given how the film ultimately turns out, the zanier parts feel just a little out of place.

In fact, I almost felt as if half of the characters inhabited a psychologically realistic movie universe, the other half inhabited a screwball universe, and Ray was caught in the middle. So, we can't rule out that this was done deliberately to emphasize the theme of Ray's uncertainty as to where he fits into the world. And if this is the case, it was a bold choice and I commend writer-director Mahmood for trying it. But I found it a bit disorienting. I also found some of the writing a bit obvious. By this I mean that some things which were said explicitly I would have found more interesting had they been gradually revealed or remained subtextual. But that's a matter of preference I suppose.

All that said, once Shades of Ray hit its stride somewhere around the third act, I was completely invested in Ray's story. Or, at least, I was far too invested to notice any more nitpicky things I didn't like about the screenplay. There are many things that separate the good romantic comedies from the massive pile of schlock that gets churned out on a regular basis, and this movies hits almost all of them. But one of those things that Shades of Ray does particularly well is to establish an interesting non-romantic conflict and weave it together with the romantic conflict. I'm sure plenty of movies have been made about people of South Asian descent struggling with their ethnic identity. But I've never seen a movie where that underlies the romance plot, and for that reason this movie felt a bit more fresh than similar ones I've seen.

It also eschews one of my least favorite conventions of the genre. Usually, in a romantic comedy, when a character needs to choose between two romantic partners, one is either a praying mantis-like gorgon, or an intolerable d-bag, and you wonder how our protagonist ended up with this miserable human being in the first place. But Mahmood actually takes the time to create two women who seem like decent enough people that Ray's decision is actually a decision.

The point is, if you decide you want to see a romantic comedy for some reason (I'm not here to judge) and want to see one that you won't feel like you've seen a thousand times before, this one is pretty good.

Writing, Act III: 7/10

Overall Originality: 8/10

Quirkiness of Supporting Characters: 9/10

Minutes Before Men In The Audience Realize With Horror That They're Watching And Enjoying a Romantic Comedy: 75/90

The Bottom Line: Though the screenplay is a bit uneven at first, Shades of Ray gradually evolves into a refreshingly non-formulaic rom-com.

Let's clear the air straightaway. In this review, I'm going to be talking like someone who is familiar with romantic comedies. Yes, I am an adult male. Yes, I identify as heterosexual. And yes, I have seen my fair share of romantic comedies. I date. It happens, you know?

Before I start my nitpicking, let me say that I genuinely enjoyed this movie. When it starts, though, Shades of Ray doesn't seem completely certain what kind of comedy it wants to be. Sometimes it tries to be a subtle, family-driven romantic comedy with psychologically realistic characters and other times it tries to be a zany, slapstick comedy with over-the-top characters. Both are equally legitimate forms of comedy. But each is watched and identified with differently, and when a single movie tries to do both, it can be hard for an audience to get its bearings. Don't get me wrong, both the zany bits and the subtler jokes are quite funny in and of themselves. But given how the film ultimately turns out, the zanier parts feel just a little out of place.

In fact, I almost felt as if half of the characters inhabited a psychologically realistic movie universe, the other half inhabited a screwball universe, and Ray was caught in the middle. So, we can't rule out that this was done deliberately to emphasize the theme of Ray's uncertainty as to where he fits into the world. And if this is the case, it was a bold choice and I commend writer-director Mahmood for trying it. But I found it a bit disorienting. I also found some of the writing a bit obvious. By this I mean that some things which were said explicitly I would have found more interesting had they been gradually revealed or remained subtextual. But that's a matter of preference I suppose.

All that said, once Shades of Ray hit its stride somewhere around the third act, I was completely invested in Ray's story. Or, at least, I was far too invested to notice any more nitpicky things I didn't like about the screenplay. There are many things that separate the good romantic comedies from the massive pile of schlock that gets churned out on a regular basis, and this movies hits almost all of them. But one of those things that Shades of Ray does particularly well is to establish an interesting non-romantic conflict and weave it together with the romantic conflict. I'm sure plenty of movies have been made about people of South Asian descent struggling with their ethnic identity. But I've never seen a movie where that underlies the romance plot, and for that reason this movie felt a bit more fresh than similar ones I've seen.

It also eschews one of my least favorite conventions of the genre. Usually, in a romantic comedy, when a character needs to choose between two romantic partners, one is either a praying mantis-like gorgon, or an intolerable d-bag, and you wonder how our protagonist ended up with this miserable human being in the first place. But Mahmood actually takes the time to create two women who seem like decent enough people that Ray's decision is actually a decision.

The point is, if you decide you want to see a romantic comedy for some reason (I'm not here to judge) and want to see one that you won't feel like you've seen a thousand times before, this one is pretty good.

Friday, August 13, 2010

I Meant To Write This A Long Time Ago

BEWARE: PHILOSOPHY AHEAD

The following article is the most verbose and pretentious thing I’ve written on this site. It’s not how I would ever write a movie review, but it’s almost exactly how I would’ve written a philosophy of art paper back in my college days. If you’re interested in the topic at hand, please try and bear with me. I promise, none of my actual reviews will be like this.

If you've spent any time trolling the interwebs for movie reviews, you've almost certainly discovered a man named Roger Ebert long before you found my modest little blog. That's because Roger Ebert is an excellent, critically lauded movie critic, and has been an excellent movie critic for a long time. Hell, he was famous for being a movie critic even before the internet existed. Imagine that!

But if you've spent time reading movie reviews on the internet, you're probably also aware of the firestorm surrounding one of Ebert's most controversial opinions. He has said, several times, that video games are not and will never be art. And while I am a cinephile like Ebert, I have also been a gamer since middle school and, as you might imagine, I disagree. But I should say at the start that my agenda in writing this extends beyond the silly desire of a young gun to one-up one of the most venerable figures of the previous generation. As a lover of both video games and movie, I would love to see someone finally make a genuinely good video game movie (Metal Gear Solid is allegedly in pre-production, so fingers crossed that they don't butcher Hideo Kojima's masterpiece), but I don't think that can happen until the high-ups in Hollywood take games seriously as an art. So what I am about to write is directed just as much at everyone in the film world who has written off video games as it is at Mr. Ebert in particular.

|

| Just, don't get me started... |

So, on to the topic at hand. Mr. Ebert has made his claim on several separate occasions. To my knowledge, the two most recent were in April of this year and July of 2007. And his position is worded slightly differently in each. In the latter he says that anything can be art, but video games can never be “high art,” as he understands it. In the former, he says that maybe ‘never’ is extreme, but “no video gamer now living will survive long enough to experience the medium as an art form.”

I’m not sure what to make of these two claims, but as far as I can see there are three main ways to interpret Mr. Ebert’s position: Either (1) Video games are in such a stage of infancy as a medium that it will be indefinitely long before they become art, (2) By saying games are not art, Mr. Ebert is really saying they are bad art, in the same way that crotchety old curmudgeon types say rap isn’t music, or (3) there is something inherent in the nature of video games (philosophers might say there is something ontological) that prohibits them from being in the same category as painting, sculpture, film, music, etc.

At a glance (1) might seem to be in line with Mr. Ebert’s statements this past April. But it doesn’t seem like a reasonable position to take for someone who knows film history, as I’m sure Mr. Ebert does. There are video gamers today who are under the age of ten. These people have life expectancies upwards of 90 years. And if you know film history, you know that’s just about how long it took for cinema to go from a cheap sideshow attraction to The Godfather. (2) might seem in line with Mr. Ebert’s statements from 2007. But he admits to never having played video games. Thus, his making such a damning, wide-sweeping evaluative statement about the medium would make him, for lack of a better word, kind of a jerk. But I don’t think Mr. Ebert is a jerk.

So, both because I have great personal respect for Mr. Ebert and because (as I mentioned before) it’s good form to give one’s opponent in a debate the benefit of the doubt, I’m going to assume he didn’t mean to be understood as saying (1) or (2). That leaves (3), which if you read the articles I’ve linked to, I think you’ll see gels nicely with most of what Mr. Ebert has to say.

So what should we say about (3)? If Mr. Ebert indeed thinks that something categorically prohibits video games from being art, it is almost certainly that they are interactive. He comes back to this point several times in those two articles. For instance, “I believe art is created by an artist. If you change it, you become the artist.” And again, “Art seeks to lead you to an inevitable conclusion, not a smorgasbord of choices.” To this I have several responses.

First, as a simple matter of fact, story-telling in video games is not as open-ended as Mr. Ebert might think. Yes, the player controls the protagonist(s). Yes, the player chooses which comically large weapon the player uses to blow up the zombies. But in most games, major plot points are pretty much set in stone. Yes, the player can fail at the game in which case the hero “dies” before s/he completes the quest. But when that happens the player doesn’t suddenly take control of the guy’s wife and kids as they sit around at his funeral. The player just gets another chance to advance towards the pre-scripted ending. In many ways, the major plot points in a story-telling video game are just as inevitable as those in a movie or novel; the only way for them to not happen is if the audience fails to make it that far. Someone not having the gaming skills to finish Final Fantasy VII is like that person not having the reading skills to finish Paradise Lost. Yes, Mr. Ebert is correct to point out that you can “win” at video games. But (in storytelling modes of video games, at least) it’s not really like the other side can win. You win at video games in much the same way that you win at watching movies if you can get through Gone With The Wind without a break.

Second, even in games that are more open-ended, such as so-called massively multiplayer online roleplaying games, what about the parts of the interactive framework that cannot be changed by the audience? Imagine, for example, an intricate chess set that had been carved by hand out of marble. Even if the act of playing chess were closer to sport than art, would the board and pieces not be art? Why then would a Hydralisk, crafted impeccably out of 1’s and 0’s rather than marble, not be art?

|

| See? Bee-ooh-tee-full |

But ultimately, I just don’t buy the claim that nothing interactive can be art. If you’ve ever been to a modern art museum, you’re familiar with the concept of installation art, in which an important component of the artwork is the order and pace at which the audience chooses to experience it. We should also note that Chris Marker (director of the obscure art-house sci-fi cult classic “La Jetee”), for instance, spent a significant portion of his career making interactive art on CD-ROM. And if that’s too new-agey for your taste, what about improvisational theater? Are actors and directors only artists if they work within a rigid script and without any input from the audience? How about the politically-motivated mode of theater developed by Brazilian director Augusto Boal, which seeks to do exactly what Mr. Ebert disparages. That is, present a tragedy to the audience and then allow them to go back and fix things to prevent the tragedy. The idea here is for the artistic statement not to be the message of the original tragedy but rather the message that people have the ability to improve their lot. I happen to agree with Mr. Ebert that, in these situations, there is a sense in which the audience becomes the artist. But unlike him, if this is done skillfully, I don’t see how it intrinsically detracts from the art-hood of the work.

I hope I’ve contributed something useful to this debate. I have taken Roger Ebert’s most recent statements about the status of video games as non-art and interpreted them as favorably to him as possible. Then I’ve shown that, even on these interpretations, there are some important things Mr. Ebert may have overlooked. Even if I’m wrong, though, and video games are never art, I will continue to enjoy them and take meaning from them, as I do with movies. Now, for the love of art, will someone please make a video game movie that doesn’t suck?

Tuesday, August 10, 2010

Update Coming Friday!

So, my computer is finally fixed, but as you might imagine I'm pretty behind on my writing. So I'm going to try to get back on my cycle starting with an op-ed piece this coming Friday. Thanks for your patience, and please stay tuned.

Friday, August 6, 2010

Whoops!

F.Y.I.: I normally like to publish an op-ed piece on Friday as a break from standard reviews. But my computer is in the shop, so today's post (keep scrolling) was a regular review that I meant to publish on Monday of next week. Those of you keeping score at home will be pleased to know that I will be publishing a very wordy, pretentious op-ed piece first thing Monday morning.

BLACK DYNAMITE (Scott Sanders, 2009)

Humor: 8/10

Editing: 10/10

Overall Aesthetics: 10/10

Quotability: 7/10

Jive-Ass Turkeys Left Around When Black Dynamite Gets Through: 0/10

Editing: 10/10

Overall Aesthetics: 10/10

Quotability: 7/10

Jive-Ass Turkeys Left Around When Black Dynamite Gets Through: 0/10

The Bottom Line: Just when I started to fear no one remembered how to make a genre farce anymore, Black Dynamite came along to take its place among the best.

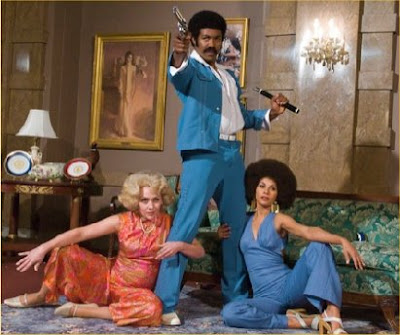

For those of you who don't know, the 1970s saw the release of dozens of B-movies which cashed in on the political frustrations of Black America at the time. These films were politically troubling in that they equated Black empowerment with excessive violence and aggressive sexuality. Also, most of them were pretty poorly-made. But they have undeniable historical importance for American cinema, and as such, continue to be studied by film historians, who have grouped these films under the genre description 'blaxploitation.'

Black Dynamite, then, is to blaxploitation movies what Airplane! was to disaster movies and Blazing Saddles was to westerns. Its hero (Michael Jai White), who is called Black Dynamite by even his dying mother in a flashback to when he was ten, is an ex-CIA agent who retired after a traumatic experience in Vietnam. He comes out of retirement to avenge the murder of his brother, who got too close to something while investigating a new street drug wreaking havoc on the Black community. So, of course, in searching for his brother's killers, Black Dynamite picks up the trail of the conspiracy his brother was on to. I won't tell you how high the conspiracy goes or with whom it ends, because that would ruin some of the fun of the absolutely priceless climactic nunchuk battle. But if Scorsese's Taxi Driver revealed the psychosis behind Charles Bronson-style conservative revenge films, Black Dynamite reveals the pathological paranoia of many blaxploitation films.

This isn't the first send-up of blaxploitation in recent years. Malcolm D. Lee attempted something similar in 2002 with Undercover Brother, which was a very funny movie. But I think Black Dynamite is more clever. That's not to say that clever is necessarily better, but it's just a different kind of humor. Whereas Undercover Brother focuses mostly on (well-written and well-delievered) fried chicken and hot sauce jokes and Zucker brothers-style sight gags, Black Dynamite mostly pokes fun at the idiosyncrasies of the films it parodies.

The excessive violence of blaxploitation gets converted here into some wonderful slapstick moments to which verbal description can't do justice. The low-production values of those films is recreated meticulously, from the high-contrast 16mm film stock to the boom mike that's clearly in the frame during a motivational speech. They say you need to be great to be a clown, in which case my hat goes off to Cinematographer Shawn Maurer and editor Adrian Younge. Take it from someone who's made films: it's not easy to intentionally shoot and edit a movie so that it looks like it was poorly made. Younge also deserves kudos for his authentic-sounding funk score. The acting is also intentionally and hilariously wooden. My personal favorite is the random thug who reads his stage directions along with his lines.

So I guess what I'm saying is that Black Dynamite is the thinking man's stupid movie. Yes, some of its jokes are academic references to obscure old movies. But will the casual movie lover still laugh out loud throughout? In the words of B.D. himself, "you bet your ass and half a titty."

P.S. If you want a crash course in blaxploitation before you see this movie, the seminal films of the genre are Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song (Melvin Van Peebles, 1971), Shaft (Gordon Parks, 1971), and Super Fly (Gordon Parks Jr., 1972).

Wednesday, August 4, 2010

IT MIGHT GET LOUD (Davis Guggenheim, 2008)

Research & Archive Footage: 9/10

Sound Mixing: 9/10

Development of Themes: 4/10

Schoolboy Giddiness: 7/10

What The Amps Go To: 11/10

Sound Mixing: 9/10

Development of Themes: 4/10

Schoolboy Giddiness: 7/10

What The Amps Go To: 11/10

The Bottom Line: Pornography for hardcore rock geeks makes for a just pretty good documentary for the casual music fan.

Shortly after the opening credits of It Might Get Loud finish rolling, we spend about five minutes listening to guitar players Jack White and The Edge talk about their differing pseudo-philosophies about the creative process. During this time, it's hard not to think about Nigel Tufnel from Spinal Tap (sorry, I don't know the html for an 'n' with an umlaut). Then, without saying anything, Jimmy Page picks up his Les Paul and plays "Ramble On," and we remember why we're watching this movie in the first place.

Disappointingly, that short sequence is representative of the whole movie, for which director David Guggenheim convinced these three real-life guitar heroes to jam together so that he could make a movie about it. There are incredible moments of rock'n'roll that keep us going, but they get bogged down by a whole lot of pretense in between. Most great rock docs focus on conflict within or amongst the artists. But Guggenheim, who was perfectly willing to challenge the world's energy conglomerates in An Inconvenient Truth, seems unwilling to challenge these musicians he obviously admires. Early on, it seems as though we're being set up for conflict as we hear Mr. White and Mr. ...Edge (seriously, dude, you're almost 50. It's time to start thinking about a last name) voice their opinions on technology. The latter thinks technology has always driven popular music forward and should be embraced, whereas the former thinks technology stifles creativity by making things too easy*. But, as far as we can tell, the two never opine on the matter in the same room; the conflict never gets developed. And if you're going to make a very talky documentary, you need to latch on to some themes and develop them fully.

Now, that's not to say that every rock doc has to be based around conflict. Scorsese's The Last Waltz is two hours of unadulterated hero worship, and it's my favorite concert film of all time. But note the ratio of music to talking in that film as compared to this one. The point is, Guggenheim could have made a good film without presenting his heroes in an unflattering light, but it would require a lot less talking and a lot more rocking than the film he in fact made.

I should say that, if you're a real music nerd like me, some of the archive gems that Guggenheim and his researchers find are priceless. There's the high school photos of Edge and Bono (and yes, Bono looks obnoxious even without designer sunglasses), there's the record Jack White recorded with his Master when he was an apprentice upholsterer. But the best one has to be the black & white footage from a 50's British talk show, in which the dorky pre-pubescent guitar player of a skiffle band tells the very straight-laced host his name is "James Page, sir."

Just to reiterate, there are some amazing music moments that even a casual rocker will love. There's something irresistibly charming about the schoolboy glee with which these three rockers talk about the people who inspired them. And, of course, for Edge and White, Page is one of those people. Neither of them say it explicitly, but the priceless looks on their faces when Page busts out the riff from "Whole Lotta Love" say it all.

And then, there's the truly inspired section when the three guitarists jam together on Zep's "In My Time of Dying." Guggenheim was smart enough to record each guitar track separately, and his sound mixer emphasizes each one individually as the camera moves around. And you can literally hear what each of them has said about his life and creative process reflected in his playing style. It is a truly great piece of music filmmaking. Unfortunately, the rest of the movie just isn't good enough to stay compelling throughout.

It Might Get Loud ends with Page, White, and Edge on acoustic guitars playing The Band's "The Weight." It's really fun to listen to, but you already know what my favorite movie involving that song is.

*Sidenote: I know why Guggenheim devoted a few minutes to this debate. Every filmmaker alive has felt this ambivalence at some point. Am I a worse editor because I take for granted being able to Command-Z a bad slice? Sometimes I honestly don't know.

Monday, August 2, 2010

RELIGULOUS (Larry Charles, 2008)

Funniness: 7/10

Scariness: 7/10

Good Questions: 5/10

Arrogance in Manner of Asking Good Questions: 9/10

Argument Construction: Worth maybe a 'C' in Philosophy 101

The Bottom Line: While no doubt a good conversation starter, Religulous falsely pretends to be a conversation finisher.

[Let's get this on the table before I say anything else about this movie: It's about an issue (namely, religion), and my feelings on that issue are going to color my impressions of this movie, just like yours are for you. That said, I'll do my best to focus my critique on how the film deals with the issue, rather than the opinions of the filmmakers.]

In a word, I find Larry Charles' and Bill Maher's treatment of the issue of religion frustrating. And not because it's one-sided. That I don't mind. There is no such thing as an "objective" movie, and the best documentaries are usually the ones that have a point to make and the guts to go through with it. I'm frustrated because they present their point so sophomorically.

Religulous makes its point by flying comedian Bill Maher around the world, having him ask people valid questions about their religious beliefs, and then chuckling at the ridiculous answers most of them give. He also makes a few historical claims that are just flagrantly false, but so has every Western ever made. Now, in discussing this film with people, I've heard some make the point the it's just poking fun and isn't meant to be taken seriously. I could almost buy this until the last few minutes, in which Mr. Maher tells us (over some very dramatic music...with Latin singing of course) that religion is evil and will lead to the annihilation of mankind if not stopped in its tracks.

So, just so we're clear on this, Religulous spends 100 minutes telling people there are questions they don't have the answers to, and then says that if we don't accept its answers, we'll all burn. Hmm...where have I heard that before? But I digress.

What I'm getting at is that the end of this film absolutely suggests that we're supposed to take it seriously. And as such, its thesis needs to be held to the standards of genuine academic discussion. Which brings me to my next point:

What I'm getting at is that, if an atheist wants to present his claim effectively, s/he needs to be able to refute religion's most competent defenders. So who does Mr. Maher interview? Alvin Plantinga and the rest of the philosophy faculty at Notre Dame? Steven Jay Gould, the Jewish-agnostic, world-renowned evolutionary biologist who has written papers defending Christianity? No. He talks to Bible Belt truckers. He talks to the actor who plays Jesus at a fundamentalist amusement park. You know, real illuminati types.

There is a very refreshing section in the middle of the film in which Mr. Maher speaks with two Vatican priests, one of whom is emphatic that religion should not be taught as science and the other of whom is dismayed at how far modern Christianity has gotten from the teachings of Jesus. But, as far as I can tell, these men have not renounced their faith or their vows. It would be very interesting to hear Mr. Maher ask them how they reconcile the frustrations they expressed with their belief in God, but we never get to hear that.

All that said, this is a film. This is Mr. Charles' film and he has every right to be as one-sided as he likes. But here's the problem. One of the main critiques of religion presented in Religulous is that it purports to give definite answers to questions about which we can never be certain; in some matters, certitude is dangerous and doubt is healthy. Accordingly, Mr. Maher repeatedly insists that he is "just asking questions." But he isn't. He's asking uneducated people difficult questions and then wringing his hands with mischievous glee when they can't answer them. The few times that he encounters someone who might actually be equipped to argue with him, he either talks over them, doesn't ask the right questions, or else Mr. Charles has his editor get rid of them. And this is done in the same breath with which the filmmakers pat themselves on the back for their own humility.

So, my parting shot for Mr. Charles comes from a Bright Eyes song that I liked very much as a teenager: "And if you swear that there's no truth, and "who cares?", why do you say it like you're right?"

P.S. Now that I'm done being a responsible movie critic, I'd like to take a moment to point out that one of the points this movie makes is an outright lie. The movie claims that it's silly to hold on to religion because we don't cling to any other ideas from the Bronze Age.

So here's my question, Misters Charles and Maher. If I showed you a right triangle in which the side adjacent to the hypotenuse measured 4 inches and the side opposite the hypotenuse measured 3 inches, could you tell me the length of the hypotenuse without having to measure it? If you can, congratulations. You're clinging to an idea from the Bronze Age.

P.P.S. It's a shame we disagree so much on this one Mr. Charles. "The Library Cop" is one of my favorite episodes of Seinfeld.

Scariness: 7/10

Good Questions: 5/10

Arrogance in Manner of Asking Good Questions: 9/10

Argument Construction: Worth maybe a 'C' in Philosophy 101

The Bottom Line: While no doubt a good conversation starter, Religulous falsely pretends to be a conversation finisher.

[Let's get this on the table before I say anything else about this movie: It's about an issue (namely, religion), and my feelings on that issue are going to color my impressions of this movie, just like yours are for you. That said, I'll do my best to focus my critique on how the film deals with the issue, rather than the opinions of the filmmakers.]

In a word, I find Larry Charles' and Bill Maher's treatment of the issue of religion frustrating. And not because it's one-sided. That I don't mind. There is no such thing as an "objective" movie, and the best documentaries are usually the ones that have a point to make and the guts to go through with it. I'm frustrated because they present their point so sophomorically.

Religulous makes its point by flying comedian Bill Maher around the world, having him ask people valid questions about their religious beliefs, and then chuckling at the ridiculous answers most of them give. He also makes a few historical claims that are just flagrantly false, but so has every Western ever made. Now, in discussing this film with people, I've heard some make the point the it's just poking fun and isn't meant to be taken seriously. I could almost buy this until the last few minutes, in which Mr. Maher tells us (over some very dramatic music...with Latin singing of course) that religion is evil and will lead to the annihilation of mankind if not stopped in its tracks.

So, just so we're clear on this, Religulous spends 100 minutes telling people there are questions they don't have the answers to, and then says that if we don't accept its answers, we'll all burn. Hmm...where have I heard that before? But I digress.

What I'm getting at is that the end of this film absolutely suggests that we're supposed to take it seriously. And as such, its thesis needs to be held to the standards of genuine academic discussion. Which brings me to my next point:

That's a straw man. People who study rhetoric and debate sometimes use the term 'straw man argument.' A straw man argument is when you present a half-assed version of the position you want to refute, and then knock it down with ease. This is usually frowned upon in serious debate. It's like if I were to argue in favor of communism by saying that capitalism boils down to "gimme gimme gimme!" Yes, there are some people who interpret and practice capitalism this way. But that just shows that those guys are jerks. Not that capitalism generally is dumb.

What I'm getting at is that, if an atheist wants to present his claim effectively, s/he needs to be able to refute religion's most competent defenders. So who does Mr. Maher interview? Alvin Plantinga and the rest of the philosophy faculty at Notre Dame? Steven Jay Gould, the Jewish-agnostic, world-renowned evolutionary biologist who has written papers defending Christianity? No. He talks to Bible Belt truckers. He talks to the actor who plays Jesus at a fundamentalist amusement park. You know, real illuminati types.

There is a very refreshing section in the middle of the film in which Mr. Maher speaks with two Vatican priests, one of whom is emphatic that religion should not be taught as science and the other of whom is dismayed at how far modern Christianity has gotten from the teachings of Jesus. But, as far as I can tell, these men have not renounced their faith or their vows. It would be very interesting to hear Mr. Maher ask them how they reconcile the frustrations they expressed with their belief in God, but we never get to hear that.

All that said, this is a film. This is Mr. Charles' film and he has every right to be as one-sided as he likes. But here's the problem. One of the main critiques of religion presented in Religulous is that it purports to give definite answers to questions about which we can never be certain; in some matters, certitude is dangerous and doubt is healthy. Accordingly, Mr. Maher repeatedly insists that he is "just asking questions." But he isn't. He's asking uneducated people difficult questions and then wringing his hands with mischievous glee when they can't answer them. The few times that he encounters someone who might actually be equipped to argue with him, he either talks over them, doesn't ask the right questions, or else Mr. Charles has his editor get rid of them. And this is done in the same breath with which the filmmakers pat themselves on the back for their own humility.

So, my parting shot for Mr. Charles comes from a Bright Eyes song that I liked very much as a teenager: "And if you swear that there's no truth, and "who cares?", why do you say it like you're right?"

P.S. Now that I'm done being a responsible movie critic, I'd like to take a moment to point out that one of the points this movie makes is an outright lie. The movie claims that it's silly to hold on to religion because we don't cling to any other ideas from the Bronze Age.

So here's my question, Misters Charles and Maher. If I showed you a right triangle in which the side adjacent to the hypotenuse measured 4 inches and the side opposite the hypotenuse measured 3 inches, could you tell me the length of the hypotenuse without having to measure it? If you can, congratulations. You're clinging to an idea from the Bronze Age.

P.P.S. It's a shame we disagree so much on this one Mr. Charles. "The Library Cop" is one of my favorite episodes of Seinfeld.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)